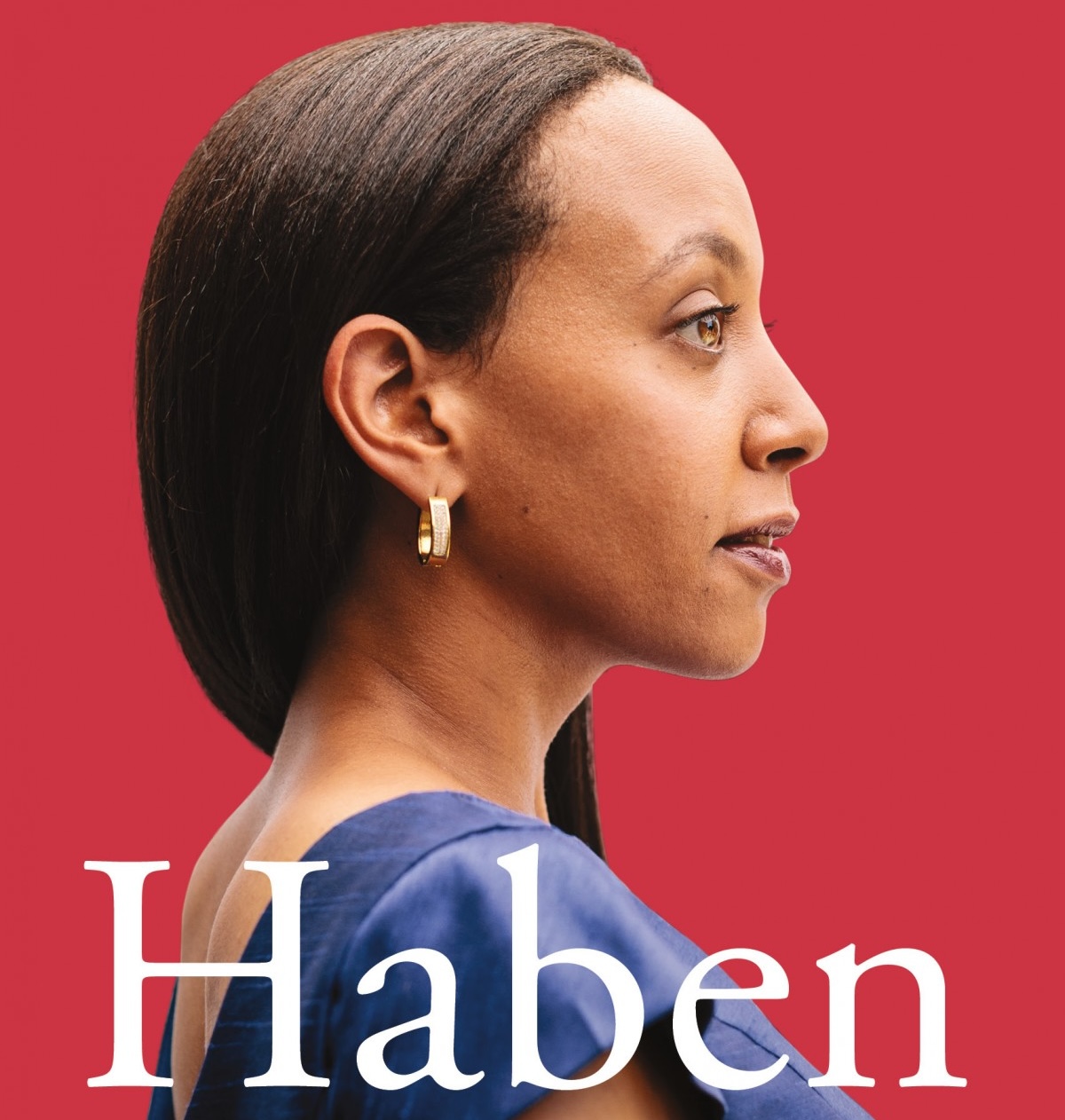

The first Deafblind person to graduate from Harvard Law School, Haben Girma is an award-winning advocate, author, and keynote speaker. She earned the Helen Keller Achievement Award, reached Forbes 30 under 30, and President Obama named her a White House Champion of Change. She believes disability challenges are opportunities for innovation, sparking new technologies that move society forward. Haben travels the globe teaching organizations how to build stronger, resilient, and more connected communities.

Her bestselling book Haben: The Deafblind Woman Who Conquered Harvard Law takes readers on adventures around the world, including training with a guide dog in New Jersey, climbing an iceberg in Alaska, fighting for blind readers at a courthouse in Vermont, and talking with President Biden and President Obama at The White House. Warm, funny, thoughtful, and uplifting, this captivating book shows how we can resist isolation and find the keys to connection. The New York Times, Oprah Magazine, TODAY Show, and Stephen Curry have all praised the book.

A spellbinding speaker, her keynotes have touched the stages of Apple, Bottega Veneta, Disney, Gartner, Google, Microsoft, Oxford University, and many more. Her engaging presentations ignite audiences to make positive changes in their communities. TIME included her as a speaker in TIME100 Talks.

In 2023 she became one of the first leaders appointed to serve as a Commissioner for the World Health Organization’s new Commission on Social Connection.

Haben was born and raised in California, where she currently lives. She travels with her Seeing Eye dog Mylo. He often falls asleep during her keynotes.

Frequently Asked Questions

What advice do you have for journalists writing about disabled people?

Challenge yourself to create a disability story without using the word inspiration. The overuse of the word, especially for the most trivial things, has dulled its meaning. People sometimes even use the word as a disguise for pity. For example, “You inspire me to stop complaining about my problems because I should feel grateful I don’t have yours.” Messages that perpetuate us versus them hierarchies contribute to marginalization. Engage audiences by moving beyond the inspiration cliché.

Harmful Messages We Should Avoid

- Non-disabled people should feel grateful they don’t have disabilities. This perpetuates hierarchies of us versus them, continuing the marginalization of disabled people.

- Successful disabled people overcame their disabilities. When the media portrays the problem as the disability, society is not encouraged to change. The biggest barriers exist not in the person, but in the physical, social, and digital environment. Disabled people and their communities succeed when the community decides to dismantle digital, attitudinal, and physical barriers.

- Flat, one-dimensional portrayals. Stories that reduce a person to just a medical condition encourages potential employers, teachers, and other community members to do the same. We are all multidimensional and participate in multiple communities.

Great Messages We Should Send

- We respect and admire disabled leaders, just as we respect and admire our non-disabled leaders.

- We can always find alternative techniques to reach goals and accomplish tasks. These creative solutions are equal in value to mainstream solutions.

- We’re all interdependent and go further when we support each other.

Read Producing Positive Disability Stories: A Brief Guide

Why should organizations invest in accessibility?

Prioritizing inclusion helps your organization. Disabled people are one of the largest historically underrepresented groups, numbering over one billion worldwide. Reaching a group of this scale creates value for everyone. Organizations that prioritize accessibility benefit by gaining access to a much larger audience, improving the experience for both disabled and non-disabled people, and facilitating further innovation. Organizations also have legal obligations to ensure access for disabled people.

What can organizations do to become more inclusive?

Numerous economic and social barriers currently exist for disabled people. A study by the United Nations found that about 97% of websites have access barriers. These digital barriers create an information famine, limiting employment and educational opportunities for disabled people around the world. Technology exists to render digital information accessible. Blind individuals use software called screen readers that allow the content of websites, apps, and documents to be read aloud or displayed in Braille on a connected Braille device. Captioning on videos provides Deaf viewers access to audio content. Programming for accessibility allows a greater number of people to access your videos, webpages, articles, apps, and other information.

Guidelines exist to help you make your information accessible. The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines is a set of technical standards for making websites accessible. To design accessible mobile apps, refer to the iOS and Android accessibility guidelines for developers. Programming for accessibility generally does not change the appearance of websites and apps. The Americans with Disabilities Act forgives those companies for whom accessibility changes would amount to an undue burden. The ADA balances all interests, ensuring creativity in the tech industry while protecting access for disabled people.

Organizations should work to create inclusive environments where all members can contribute their talents. Including disability in diversity training, increasing recruitment of members with disabilities, removing architectural barriers, communication barriers, and digital barriers will help your organization move in the right direction.

Email [enkode text=”Javascript required to display email address.”][email protected][/enkode] to arrange disability & inclusion training for your organization.

Why did you decide to become a disability rights lawyer?

As a Deafblind student in college, I witnessed advocates using the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) to change social attitudes. The National Federation of the Blind regularly referenced the ADA when explaining to technology developers why designing access for people with disabilities is a necessity. I heard how the National Association of the Deaf used the ADA to increase closed-captioning online, and how Disability Rights Advocates used the ADA to compel Target’s tech team to make target.com accessible to blind Americans.

Impressed by the success of these advocates, I felt inspired to join them. Back then, and even now, I encountered many barriers in the digital world. Not because of my disability, but because of attitudes among tech developers that trivialize access for disabled people.

Learn more through my TEDx Baltimore talk, Public Service Lawyers as Pioneering Advocates.

What advice would you give to someone who aspires to go into advocacy?

It’s really important to spend time with the community you serve. Strong advocates understand the needs of their communities and have the advocacy skills to communicate those needs to others.

How do you pronounce your name?

Haben: (“Ha” like “ha-ha,” and “ben” like “Benjamin”)

Girma: (“Gir” like “girl,” and “ma” like “karma”).

I am so confused. Ethiopians say you are Ethiopian. Eritreans say you are Eritrean. What in the world are you?

It’s complicated, I know. I was born and raised in California. My father grew up in Ethiopia, and my mother grew up in Eritrea. I identify as an American with Eritrean and Ethiopian heritage.

Have you ever won a legal case?

Of course! I represented the National Federation of the Blind in a lawsuit seeking to get the digital library Scribd to make its services accessible. Because of the design of the Scribd website and apps, blind readers could not access many of the books and documents. Scribd argued that it didn’t have to make its services accessible, claiming the ADA doesn’t apply to websites and apps. Disagreeing with Scribd, the Court ruled in our favor. “Now that the internet plays such a critical role in the personal and professional lives of Americans, excluding disabled persons from access to covered entities that use it as their principal means of reaching the public would defeat the purpose of this important civil rights legislation,” the Court wrote. Scribd soon agreed to make its digital library accessible. Working on this groundbreaking case to help blind readers gain access to books was one of the most rewarding moments in my legal career. You can read the full court decision here: NFB v. Scribd.

In 2016 I stopped litigating cases to focus instead on educating organizations on the benefits of choosing to practice inclusion.

You’re just like Helen Keller! What do you think of her?

People pressured me to adopt her as a role model and I resisted. When I reached college, I finally took the time to learn about Helen on my own terms. Reading about her work, I felt so much admiration and respect.

The danger of a single disability story is that the public expects people to conform to that story. My story is one more story from which the public can learn, and I hope having more disability stories will get people to stop saying, “You should be just like ‘X.’” We all deserve the opportunity to develop our own unique talents and interests. It’s not fair to tell someone, “You should learn to surf because Haben surfs.” Such statements pressure people to conform to a single story, a single set of expectations. That’s incredibly limiting.

Forcing role models on people doesn’t work. Instead, take the time to listen to the dreams of your friends and help them find ways to transform them into reality.

How did you learn to speak when you’re Deafblind?

Deafblindness encompasses a wide variety of different types of hearing loss. I have some hearing in the high frequencies and trained myself to speak in a higher voice. Hundreds of experiences on stage, from theatre classes to TEDx, have helped me master the art of public speaking. Most recently, Penny Kreitzer is a phenomenal voice coach who helped me prepare for my remarks at the White House.

How did you overcome your disability?

My disability is not something I’ve had to overcome. I’m still Deafblind. The biggest barrier I face is ableism, the widespread beliefs and practices that value nondisabled people over disabled people. My success at school, in the office, and even on the dance floor were facilitated by communities that chose to do the work of dismantling ableism.

How do you communicate with people?

How I communicate with someone depends on the skills we share. Written English is my strongest form of communication, so if the person I am communicating with knows written English and can type, that’s what we’ll do. The person types on a wireless keyboard that outputs to a braille display. I read as the person types. If the person understands spoken English, then I’ll voice my end of the conversation. Depending on the person’s abilities, i may use sign language, type text, voice in another language, or work with an interpreter.

Adapting to the abilities of others and the restraints of the environment are essential to communication. My guide dog, unable to use spoken English, will nose-nudge my hand to request my attention. Salsa dancers, unable to type while dancing, convey music and motion through their hands. Learning the language of salsa and other partner dances has placed me within a community that communicates joy through movement and music. Whether through movement, written words, spoken words, or other cultural symbols people connect when they search for shared symbols and adapt to each others’ abilities.

What do you fear?

I fear fear’s power. Fear fuels all the injustice in our world. Fear stands behind all the pain experienced by those marked as “others” by a majority group. Fear freezes compassion that would otherwise build bridges between all our unique lives. Pushing aside fear, I celebrate the growing number of people who recognize our shared humanity.

Can you watch movies?

I access movies by reading the screenplays, which have written dialog and visual descriptions. Since movies hold a central place in our culture, I try to read the screenplays of all the major ones.

Is there anything you can’t do?

I can’t cartwheel. Every now and then I will experience a moment of pure joy and wish I could leap into the air and gracefully glide my feet over my head, but I can’t. I know that I could probably conquer the cartwheel if I hired a personal gymnastics trainer, but I have chosen to use my time to advocate for disability justice.

Have more questions? Send them to [email protected]