Surfing as a Deafblind person feels like I’m alone with the ocean. The exhilaration of connecting with such a powerful force of nature is unlike anything else I’ve experienced. My whole body listens to the ocean through the board, constantly adjusting as it tilts and sways. I can’t see where the ocean takes me, but I ride anyway, trusting that everything will work out. I know that my water guides are somewhere nearby, ready to help when I need it.

My surfing journey began in high school when a nonprofit called Ride-A-Wave introduced me and other kids with disabilities to the joy of tandem surfing. The waters of Santa Cruz felt freezing, but I still wanted to go back. Tandem surfing has a beautiful communication aspect that comes from sharing a surf board with someone. Over the years I did more tandem, all while wondering if it would ever be possible for me to surf on my own board. I tried some tentative lessons with Surf Diva and Richard Schmidt. Solo surfing started to feel possible, and I began imagining myself riding the warm waters of Hawaii.

Access Surf Hawaii turned that dream into a reality. It was a dark and stormy day, but we hit the waves anyway. The waters of Waikiki still felt warm despite the pouring rain. Ryan coached me through the process of standing up on a moving board, using a combination of voice and ProTactile to communicate. Eddie stayed nearby as I rode the waves, swooping in to guide me whenever I wiped out. I surprised myself by not only standing up, but riding waves for a good long while. I’m incredibly grateful to Access Surf Hawaii for braving the rain to help me grow as a surfer. I will carry these marvelous memories with me into 2019 as a reminder to keep daring myself to go further than I’ve ever gone before. Mahalo.

Video Description

A Seeing Eye dog sits on a sandy beach as he stares longingly at the ocean. The pointy ears of the German Shepherd are even twitching. The sound of crashing waves is loud and powerful. Mylo squints and stares, searching for his human. The camera pans to the water.

This scene has about twenty surfers in the water. Three begin riding a wave. One fist pumps and topples over. Another sits down cautiously. Haben rises to her knees, then her feet, spreads her arms out, and rides the wave all the way.

Mylo spots Haben and Ryan walking out of the water. His tail wags furiously as he runs over to Haben and begins licking her.

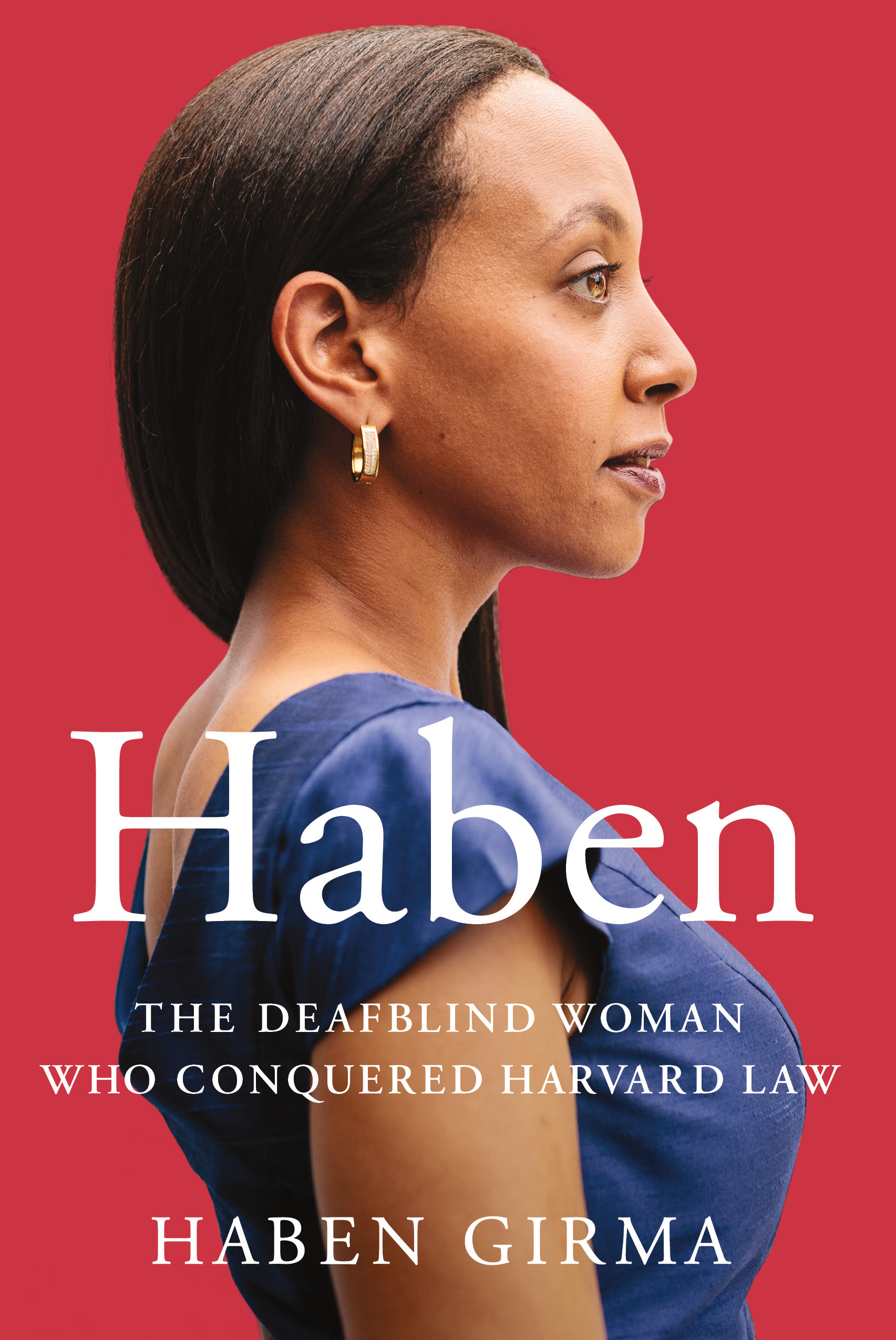

Photo of Access Surf Hawaii members Eddie Murai, Aaron Murai, Ryan Chahanovich, and Haben and Mylo. They’re all smiling and standing in front of surf boards.